Navigating Your Career

The end of the year is a time of reflection. It’s a chance to ask, “How has the last year gone? What have I achieved? What do I want for…

The end of the year is a time of reflection. It’s a chance to ask, “How has the last year gone? What have I achieved? What do I want for next year?” As you wrap up your 2021, you might be looking specifically at how your career is progressing. Are you tracking towards your goals? Are you happy with your career trajectory? If you’re not, how can you get back on course?

Getting answers to these difficult questions is inherently introspective. Only you have the answers, and only you can do the work of reflecting. No two people think about their work, their goals, and the vision for their career in quite the same way. At first, the prospect of setting and following career goals can seem daunting, but with some principles for thinking about your career and some rituals to regularly assess your progress, what seems amorphous can become concrete and actionable.

A caveat is that things change — all the time. You change. Your work changes. The world changes. Your situation changes. How you feel today might be different from how you feel tomorrow. You might have to move across the country, receive an unexpected job opportunity, get laid off — or suddenly have to endure a global pandemic. It’s important to know when your situation or you have changed and to adapt over time. But no matter what’s happening personally or what choices you’re making professionally, you are charting a course and navigating toward something.

It’s also possible that perhaps you haven’t thought too much about your career goals — yet. Early in your career, you might not yet know if you’re on the right path for you or where you’d like to be in 1 year, let alone 5. You may not even be sure how to start thinking about something as big and vague as “What do I want to do long-term? What is my ideal working situation? How do I get there?”

In this article, the Merit team presents three principles and three rituals to help you approach your career in 2022 — and beyond.

Principles

When navigating your career, you first have to decide where you want to go — or at least in what direction you want to head. Determining your direction leans on three principles: understanding what work means to you, learning about your work likes and dislikes, and then being fixed on a mission while being flexible on the details.

Understand what work means to you: A first step in navigating your career is writing a work mission statement by understanding what role work plays in your life (like everything, this might change!). For some, work fulfills a personal mission, like being creative, following their curiosity, building cool things, or solving difficult problems in an industry they care about. For others, work is a way to earn enough to fund their passions outside work and doesn’t play a central role in meeting emotional needs.

One way to think about these needs is what is at the core of your desire (and need) to work? What motivates and drives you? Leslie Luo, a senior product designer at a large tech company, describes it this way, “At the end of the day, I need something that really drives and digs into my curiosity.” What do you need? This is your mission in working.

An important distinction is that these needs are aspirational and separate from fundamental needs like affording food and housing or, depending on your situation, maintaining your immigration status. The process described here focuses on once all your basic needs are met.

Evaluate yourself on the axis: Even if the mission of your work is to fund your passions outside of your day job, that day job fills the majority of your working hours, so you want to avoid dreading your day-to-day.

Whether your tech career fulfills your personal mission or not, building an understanding of what you like and dislike as well as the kind of work you do well at will help you determine what kind of jobs and work are best for you.

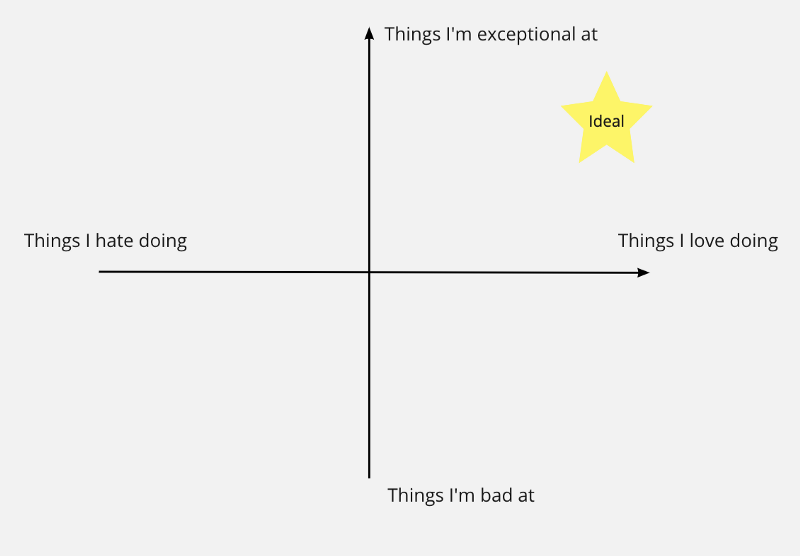

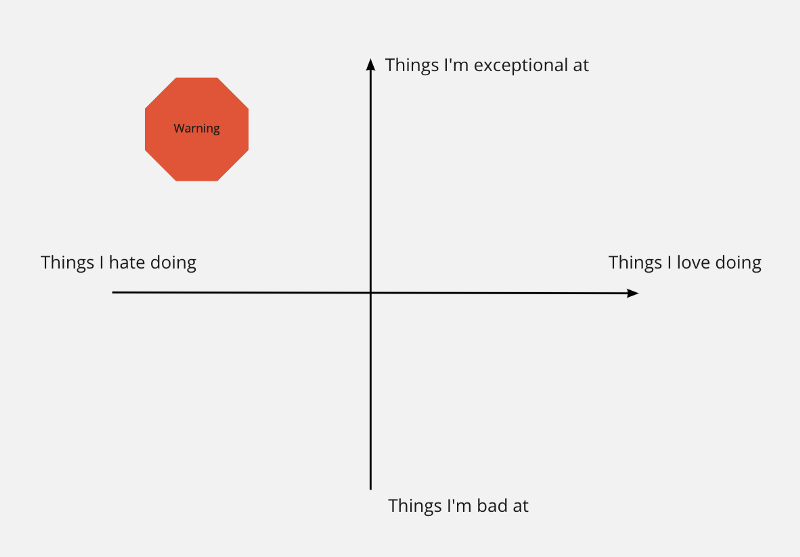

In an article for First Round on driving career conversations, Molly Graham, formerly of Google and Facebook, encourages keeping four lists as you work, which we at Merit have organized into a matrix. Plot out your work activities and tasks on a scale from “Things I hate” to “Things I love” and from “Things I’m exceptional at” to “Things I’m bad at.”

Your ideal job’s responsibilities are an overlap between what you love doing and what you’re exceptional at.

However, it’s not uncommon to end up doing a lot of things you’re exceptional at but hate doing. As you become more senior, your work may have a greater overlap between “Things I hate” and “Things I’m exceptional at.” Avoid these opportunities — it’s okay to turn down roles or jobs you’d excel at but not enjoy.

As you fill out the matrix above, you can take it to your manager so that you can work together on incorporating more of the work you enjoy and do well in.

Be fixed on the mission but flexible on the details: For Nastia Kobzarenko, Senior Brand Designer at Policygenius, that meant knowing what she wanted in her work but letting the details form over time: “I knew I wanted to do some sort of creative career, but I didn’t know exactly what that would be.” She went between illustration, animation, and design work and experienced trial and error before landing in design.

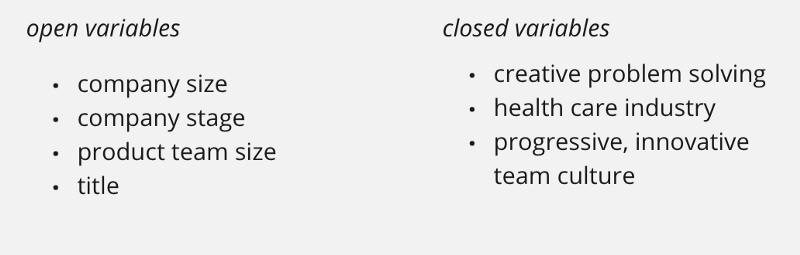

Consider “open” and “closed” variables to provide some concrete parameters around staying true to your mission while remaining open to many opportunities. Open and closed variables indicate what you’re willing to compromise on, and what’s non-negotiable.

Kirk Fernandes, the co-founder of Merit, describes this in the feeling he had about working in mentorship and representation in tech: “I was very adamant — once I realized I wanted to work in this space, on this problem, I was pretty variable on everything else.” If you’re an engineer, you might be intensely driven to build interesting technology, but the industry itself may be less important. If you’re a product manager, you may want to be solving problems in a specific space but be more flexible on the size of the company.

Below is an example of a product manager’s potential “open” versus “closed” variables:

Rituals

However, what you learn from thinking about these three principles isn’t one-and-done. You may learn to love something you previously hated, and you may come to dislike work you once loved. Each job, project, and role will add data points to your matrix. Points within the matrix can migrate quadrants or move along axes. Regularly reassessing is key. You can stay in tune with yourself and your goals by checking in regularly, gathering data, and setting short-term goals. Every season, set aside a week to reflect and do these three things.

Check-in on a set cadence: At least quarterly (and maybe more often!), write down and answer the following questions, which are a mixture of recommendations from Graham and Fernandes:

- What were the highlights and favorite things I did of the past quarter? Why?

- What moments or weeks did I feel my best?

- What did I feel like I could keep doing the same set of things over and over and be happy?

- When did I feel drained or depleted?

- When did I feel bored?

- When did I feel like my worst self?

- What was I grateful for? Why?

- What am I looking forward to next quarter? Why?

- What would make the next quarter really great? Will I think that will happen — or not?

Keep the responses to this list in a central place: a Google Doc, an Evernote, an old-fashioned physical notebook. Occasionally re-read previous entries and try to spot trends and patterns.

An important question to revisit is “What am I looking forward to next quarter? Why?” Fernandes notes, “You should always have something to look forward to, and if you don’t, that’s a bad sign.”

Through these check-ins, you may find that you’re not happy in your current role. First, ask yourself why. Is this situation temporary or permanent? Maybe you’re working on a project you really don’t like — but it will end in a few weeks. In that case, it might be worth sticking it out. But maybe the company’s culture has shifted, and you no longer feel comfortable in the new environment. If the culture doesn’t look like it will course-correct soon, it might be time to move on.

Get perspective from your network: This reflection doesn’t have to happen in a vacuum. Your friends, manager, coworkers, and mentors can all point out times that you seemed happy, demotivated, or frustrated. Feedback from those closest to you can provide strong indications that you’re enjoying where you’re heading or that maybe you need to move in a new direction.

Set short-term goals and ask why: Knowing what you’d like your career to look like in 5 years can feel impossible. Tech moves at a rapid pace. The jobs and career paths of today may look dramatically different tomorrow. A project at work may show you that you really love something you thought you’d never enjoy. Instead of fixating on exactly where you think you should be in 5 years’ time, set a goal for the next 6 to 12 months — and ask why. If the goal is to get a promotion in the next review cycle, is that because you’ll be taking on new responsibilities you enjoy? Because it’s a stepping stone to your long-term ideal role?

Making a Job Change

If, after reviewing your self-check-ins, you realize that your job and work is no longer the right fit, how do you move forward? You can’t rely on your manager and coworkers to help you decide what opportunity would be the best next step for you. Before you begin searching for a new role or sign an offer, it’s helpful to think about “push” and “pull” factors.

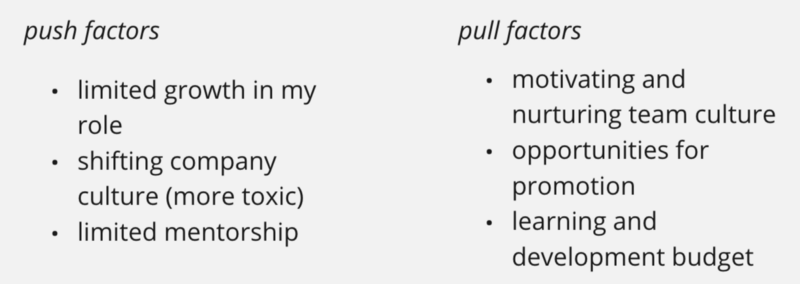

Push factors are those that are forcing you out of your current role. You can ask yourself, “What are you running away from?” Maybe you’re looking for growth and a more senior role, and at your current company, that won’t be possible for over a year. Maybe being aligned with the company’s mission is critical to you, and the company’s mission has recently changed.

Pull factors, meanwhile, are what is drawing you toward a new opportunity. If curiosity is at the core of your career path, then maybe you’re attracted to roles that pique your curiosities. If you’re looking for a role that better aligns with commitments outside work, you might be pulled toward opportunities that offer a stronger work-life balance.

In the lists below, a hypothetical engineer lists out their personal push and pull factors:

It can help to write out your criteria for a new opportunity and what those would look like in practice. Andrew Hoang, Product Lead at Ōuro, was highly specific when searching for his latest role. He narrowed his criteria down to five aspects and included both the principle that mattered to him and how it would look tactically. For example, he wrote that he wanted to allow himself “to be crazy strong-minded about how the world should work and execute on that. Tactically, the company is still early and fairly high growth.” For someone who wants to learn from more senior folks in their field, this might mean looking for a larger, later-stage start-up with a fairly large, mature team in your discipline.

Get help

If you feel like your manager isn’t giving you the guidance you’re looking for, or if you’re searching for a new job and don’t know quite what to look for next, reaching out to a mentor is a great step. Merit mentors can help you with navigating your career, setting goals, and reflecting on your career journey.